The Global Impact of Antibiotics Overuse in Livestock

Q&A with Aleks Engel

Aleks Engel has been a Partner with Novo Holdings, a Danish life science investment firm for more than 11 years working from both Copenhagen and Boston. He is currently focused on planetary health, which includes sustainable agricultural solutions. He previously led the firm’s investment activities in human health infectious diseases focusing on antimicrobial resistance. Prior to joining Novo Holdings, Aleks was employed by Baxter International, Pfizer, Truven Health Analytics, and McKinsey & Company. Dr. Engel holds a Ph.D. in Biochemical Engineering (1999) and a M.Sc. in Chemical Engineering Practice (1995) both from Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Tom Mahoney: Thank you for joining me for this discussion, Dr. Engel. Overuse of antibiotics in commercial livestock production has become one of the most urgent, complex contributors to the global antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis. Despite decades of scientific warning, the practice is expanding across both industrialized and developing markets, often driven by economic pressures to maintain animal health and accelerate growth in high-demand food systems. Resultant proliferation of resistant bacteria now compromises efficacy of life-saving medicines, endangering human health and placing immense strain on healthcare systems worldwide. Before we dive into policy and practice specifics, could you give us an overview of how Novo Holdings is addressing this challenge? In particular, how are you working to reduce antibiotic dependence in livestock production and mitigate the human health consequences of AMR - especially among vulnerable populations in low- and middle- income countries (LMICs) in a world in which WHO estimates 1 in 6 bacterial infections is now antibiotic resistant?

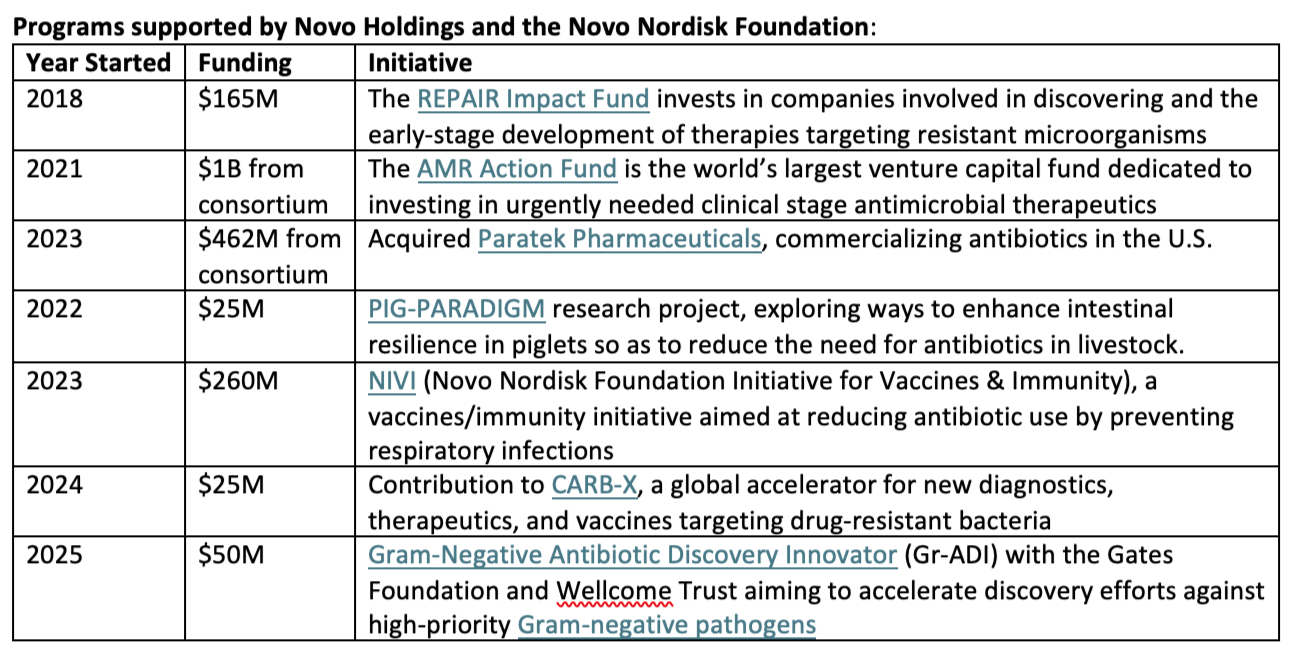

Dr. Aleks Engel: The Novo Nordisk Foundation and its investment firm, Novo Holdings, chose to embrace AMR as an area of strategic priority in 2018. As a self-owned institution with a very long-term view and investment horizon, we wanted to make a difference at a time when most investors were hastily fleeing the space. The way we work is through a series of strategic investment programs into which we have pledged about half a billion dollars (see more detail below). These programs aim to accelerate novel solutions for both human and animal health. We are proud of what we have achieved so far, but much more is needed.

The Threat to Human Health

Mahoney: Decades of research link agricultural antibiotic use to drug-resistant bacteria threatening human medicine. Could you walk us through the mechanisms by which excessive antibiotic deployment in livestock operations accelerates resistance, and how these microbes move from farms to human populations? A dramatic example in recent decades is the previously heavy use of colistin - a “last resort” antibiotic for multi-drug resistant bacteria - in commercial hog production in China, where despite ending the practice in 2017, the key colistin resistance gene in human microbiota has diffused globally, a disturbing reminder of the persistence of resistant pathogen mutations and their environmental dissemination.

Engel: When antibiotics are routinely administered - whether to promote growth, prevent disease, or treat infections - susceptible bacteria are killed, but resistant strains survive and multiply. These resistant bacteria can then spread from animal to animal, through contaminated meat, or environmental pathways such as water, soil, and air. Genes conferring resistance can also transfer between bacterial species via horizontal gene transfer, compounding the problem. As a result, antibiotic use in agriculture not only undermines the effectiveness of critical drugs for animal health but also poses a major threat to human medicine, as resistant pathogens reach and infect humans.

Mahoney: As treatment options become more limited due to resistance, what are the implications for common bacterial infections previously easily curable?

Engel: Today more than one million people die per year globally from resistant bacterial infections with around 5 million more deaths in which AMR plays a contributing role. By 2050, those numbers are projected to growth to about 2 million and 8 million respectively or about 10 million in total, which would be a larger number than deaths due to cancer.

Mahoney: Which global populations are most vulnerable to illness from resistant infections, and why are these demographics disproportionately at risk?

Engel: Unfortunately, AMR hits the most vulnerable the hardest. Those are neonates, elderly, those already sick with another disease, those without access to adequate healthcare, the poor, the unvaccinated, and the immunocompromised. These are individuals who must have well-functioning antibiotics to clear their infections.

Economic Burden of the Crisis

Mahoney: What does the rise in antibiotic-resistant infections mean for healthcare costs globally, particularly in resource-limited settings, as antibiotic resistance is often described as a “disease of inequality”?

Engel: The World Bank has estimated that the cumulative cost of the AMR crisis between now and 2050 is on par with the cost of the 2008 financial crisis or about $100 trillion (i.e. several trillion per year). The direct financial burden is about 2.0% of total healthcare costs in LMICs vs 0.4% in developed nations.

Mahoney: Beyond direct healthcare spending, how does antibiotic resistance affect economic productivity and workforce participation?

Engel: As you imply, while direct healthcare expenses (hospitalization, drugs, diagnostics) are the most visible, the biggest long-term burden of AMR lies in lost productivity, reduced workforce participation, and slowed economic growth. This stems from longer hospitalization, more deaths, and more complications and disability (think amputations and the like). And again, the sharpest impact is on LMIC workforces that rely on healthy labor for economic advancement.

Food Security and Safety Concerns

Mahoney: To what extent do resistant bacteria in meat and dairy products pose a risk to consumer health and food safety?

Engel: These pathogens exist at a critical interface between agricultural antibiotic use and public health. Consumers may be exposed by handling raw meat, consuming undercooked products, or ingesting unpasteurized dairy, allowing resistant strains - or their resistance genes - to enter the human microbiome. Once transmitted, these bacteria can cause infections that are difficult or impossible to treat with standard antibiotics. The most common bacteria involved, Salmonella, Campylobacter, and E. coli, cause millions of gastrointestinal, urinary tract, and bloodstream infections every year. And again, the risk is particularly acute in regions with weak food safety systems, inadequate cold chains, or poor hygiene standards.

Ethical and Equity Considerations

Mahoney: Routine, low-dose use of antibiotics in livestock for growth promotion raises ethical questions. How should we balance animal welfare with agricultural efficiency?

Engel: Administering even low doses of antibiotics prioritizes short-term economic gain over long-term societal well-being, violating principles of stewardship and justice, as it externalizes health risks on consumers and future generations. Since effective solutions exist on how to avoid this problem, it is really not an ethical dilemma, but a question, which has a right and wrong answer.

Environmental Impact

Mahoney: How does the release of antibiotics and resistant bacteria from livestock farms to soil and water affect surrounding ecosystems and biodiversity?

Engel: In short, it is a disaster. First, as you point out, it is both the resistant bacteria cultivated on the farm but also the unmetabolized antibiotics (typically more than 50%) that are released. Second, both of these when released into soil or water drastically reduce the biodiversity of the ecosystem resulting in many fewer but nastier bacteria through a process called microbial biotic homogenization. Third, these practices disturb the established balanced nutrient pathways such as zooplankton production and water purification systems such as nitrifying bacteria. Finally, these disturbances propagate up the food chain, altering larger species and plants in highly unpredictable ways. In some sensitive areas, even small amounts of these powerful agents can completely destroy the ecosystem. Major antibiotic-related ecosystem disasters include microbial collapse, and fish kills in China’s Yangtze River Basin, mangrove biodiversity loss in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, soil degradation in European farmlands, antimicrobial resistance hotspots in India’s Ganges River, and many more.

Mahoney: What evidence exists that resistance genes are spreading through soil and water systems, through manure and wastewater runoff, and what are the long-term environmental risks?

Engel: We have known that antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) spread through soil and water systems primarily via horizontal gene transfer among environmental bacteria exposed to antibiotics from agriculture, sewage, and industry for a long time. Back in the 1970s and 1980s, several studies from Scandinavia and the U.S. showed that plasmids carrying resistance genes were transferred from manure to soil bacteria. It was later shown that these resistance genes then spread further from there via aquatic systems and were able to pollute whole watersheds.

Addressing the Crisis - Potential Solutions

Mahoney: Reducing antibiotic use in livestock is easier said than done. What are the most realistic pathways to achieve this goal while protecting farmer livelihoods, especially in LMICs?

Engel: Yes, there is no “easy fix”; what is required is a multi-pronged approach. Let me highlight my top five suggested interventions to ameliorate the situation:

Reduced use of antibiotics in animals from accelerating best practices. Farmers can indeed rear animals without use of antibiotics and do so profitably. Norwegian salmon farmers abandoned antibiotics in the 1990s and still grew their industry to be world-leading. PIG-PARADIGM, an initiative funded by us, is teaching best practice methods for profitable sustainable pig farming around the world.

Separate drug classes used by humans and animals. Feeding “last resort” drugs like colistin, carbapenems, and linezolid to pigs is insane. If we can’t ban all antibiotics, then at least ban these highly advanced compounds. If farmers have to use antibiotics to save the life of an animal, they should use classes of drugs reserved for that purpose and not used by humans (classically ionophores and pleuromutilins).

Promote use of non-antibiotic therapeutic solutions. Examples include zinc and vinegar to treat E. coli infections in pigs. Another example is binding proteins that work as anti-virulence factors adsorbing all of the bacterially secreted toxins without putting genetic pressure on the pathogens.

Push for novel solutions specifically for animal health. Phages are the prime example here. First, phage therapy is relatively weak compared to antibiotics killing about 10% of pathogens relative to much more efficacious small molecule antibiotics due to the much larger size too that cannot extravasate (leave the bloodstream to move into tissues) to remote sites of the body. Human clinical results have been terrible because for ethical reasons, trials of new solutions have to be conducted against standard of care and not placebo. But even this amount of reduction in pathogen population is fine for relatively healthy animals. Also, the phage display libraries can be kept completely separate between humans and animals as there are plenty to go around.

Policy work. This includes promoting responsible antibiotic use in both humans and animals as well as improving global surveillance. It is critical to educate healthcare professionals, veterinarians, and the public about the importance of using antibiotics only when necessary and completing the full course of treatment. Simultaneously, it is important to know what the local prevalent resistant pathogens are, and how best to treat them.

Mahoney: We’ve seen some large U.S. meatpackers reportedly reintroduce selective antibiotic use after previous phase-outs. What does this suggest about the challenges of sustaining progress?

Engel: This is obviously disappointing news, with the excuse that is often offered that the antibiotics are used only therapeutically to cure a disease and that further not curing the disease would be unethical. I disagree with this self-serving reasoning since better solutions exist.

Mahoney: Beyond livestock, what role does responsible antibiotic stewardship in human medicine play in the broader fight against resistance?

Engel: Stewardship has been a cornerstone in prescribing antibiotics since the beginning. The critical elements are to get an accurate diagnosis as quickly as possible and then prescribe the most appropriate medicine to quickly and effectively eliminate the infection completely. Embedded in the word “appropriate” is the essential notion to hold back the big gun antibiotics of last resort. Rapid point of care diagnostics is the most exciting new development in this field.

Mahoney: How can greater global investment in R&D for new antimicrobials and alternatives - such as vaccines - help mitigate this threat?

Engel: We have been in an arms race with microbes since the introduction of penicillin. We have been slightly ahead in the race until now, but we are rapidly losing ground. To stay ahead, we need about one novel antibiotic solution introduced at least every 18 months. Vaccines are disproportionally more powerful because they have the potential to eliminate disease and resistance risk, however, they are also more expensive to develop.

Mahoney: What improvements are needed in global surveillance and data sharing to better track and respond to emerging resistance patterns?

Engel: In short, funding and political will are required. We showed during the Covid-19 pandemic the value of surveillance for both disease risk mitigation and treatment development. We have all the necessary technologies. We now need governments around the world, including our own, to acknowledge the profound risk of infectious diseases (and those resistant to existing treatments in particular). Antimicrobial resistance is the slow-motion collapse of modern medicine and the most effective low-cost solutions to the problem start in animal health.

Mahoney: Our conversation has illuminated a hopeful path forward: that through evidence-based regulation, innovation in animal health and husbandry, and sustained international cooperation, we can align agricultural productivity with preservation of antibiotic effectiveness. Balancing the needs of commercial food production with the imperative to curb resistance is critical for preserving one of the world’s most valuable assets, our miracle drugs called functional antibiotics, but our shared commitment to sustainable, science-forward solutions give reason for optimism about the road ahead.

About the Author:

Tom Mahoney, a 2024 Senior Fellow at the Harvard Advanced Leadership Initiative, is focused on global venture philanthropy initiatives to catalyze investment in development of breakthrough vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics for infectious diseases. A career investment banker, technology entrepreneur and asset management senior executive, Tom is a member of the Advisory Board of EdJen BioTech, LLC, a developer of novel viral vaccines, and Virufy, a respiratory disease diagnostics platform; a Founding Sponsor of the Harvard Alumni Entrepreneurs Accelerator; and a member of the Venture Board of the Harvard HealthLab Accelerators, the Massachusetts Consortium on Pathogen Readiness, and the Council on Foreign Relations.

This Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.