All In: The Federal Government’s Plan to Tackling America's Homelessness Crisis

A Conversation with Jeff Olivet (Part 1)

Jeff Olivet is the executive director of the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH). He has worked to prevent and end homelessness for more than 25 years as a street outreach worker, case manager, coalition builder, researcher, and trainer. He is the founder of jo consulting, co-founder of Racial Equity Partners, and from 2010 to 2018, he served as CEO of C4 Innovations. Throughout his career, he has worked extensively in the areas of homelessness and housing, health and behavioral health, HIV, education, and organizational development. Jeff has been principal investigator on multiple research studies funded by private foundations and the National Institutes of Health. Jeff is deeply committed to social justice, racial equity, gender equality, and inclusion for all. He has a bachelor's degree from the University of Alabama and a master's degree from Boston College.

Determining the size of homeless population in the U.S. is not as straight forward as you might think. Thousands of people enter and exit homelessness on a given day, so depending on the type of survey method — a single point-in-time count or other — most recent estimates suggest it’s somewhere between 580,000 and 1.3 million people. But despite the challenge of arriving at a precise number, the following are indisputable facts about the nature of that population.

Homelessness is disproportionately impacting minority and marginalized people.

People with preexisting health conditions are more likely to experience homelessness, and homelessness worsens health.

The number of people that enter homelessness each year exceeds the number that exit.

Jeff Olivet serves as the executive director of the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) and recently participated in a two-day deep dive on health and homelessness that was sponsored by Harvard’s Advanced Leadership Initiative. This interview seeks to recapture some of the highlights of his presentation and aspires to explore the topic more broadly.

Paige Warren: In December 2022, the Biden-Harris administration released “All In: The Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness.” Can you talk about the plan’s scale, focus, and priorities by contextualizing it relative to what’s come before?

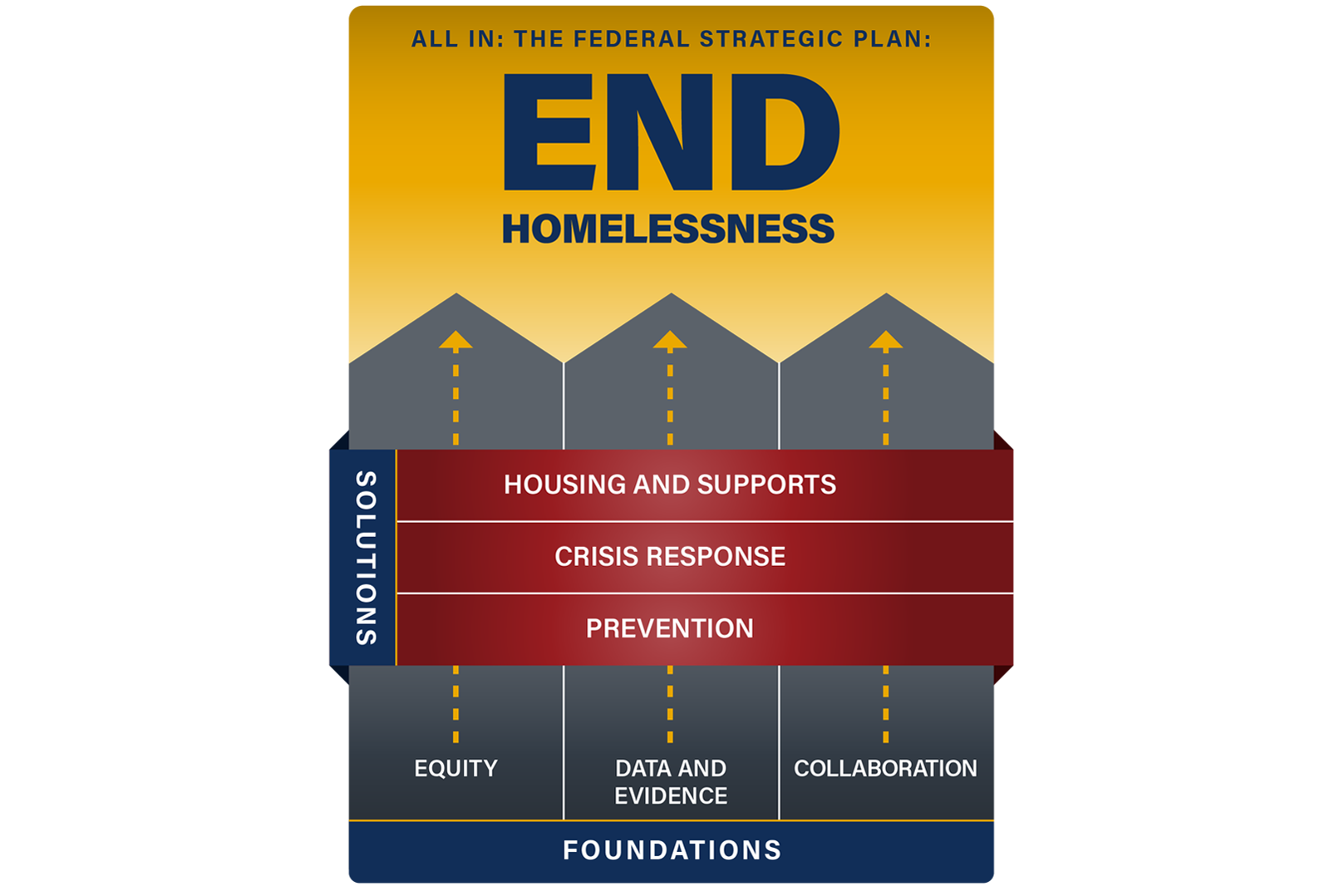

Jeff Olivet: The administration’s plan sets forth an ambitious national reduction target to reduce homelessness 25% by 2025. It is built around three foundational pillars and three solutions pillars.

The foundational pillars are to lead with equity, to focus on data and evidence, and to shore up collaboration across all levels of government (federal, state, and local), across public and private sectors, and across systems. The solutions are to prevent people from losing homes in the first place, to improve our crisis response for when they do, and to scale up housing and services to help people exit homelessness.

If we can do all three of those things at once, we can both address the crisis of homelessness we have in front of us right now and close the doors to homelessness so fewer people ever experience it. Only then can we really begin to see meaningful reductions in the overall numbers.

We tried to take the best of previous plans across multiple administrations and carry forward the things that are working and then chart new territory. A lot of the new territory that we're charting is around both upstream prevention and racial equity.

Warren: The administration’s plan is rooted in the philosophy of “housing first,” which I understand has been employed in other countries, like Finland, with notable success. What does it mean and how does it play out in application in the U.S.?

Olivet: “Housing First” is a long-standing approach that is grounded in the belief that housing is the fundamental solution to homelessness. Without it, every other aspect of a person’s life can suffer. But it's not the only solution. We need to make sure that people have access to wraparound supports that help them stay housed, like health care (including mental health and drug and alcohol treatment), job training and placement, and education support. Housing First programs offer people these supports at the same time as housing, and they continue to offer them long after people are housed.

When I got into this work almost 30 years ago, we did not have “Housing First.” At that time, we set up a lot of hurdles (such as sobriety or employment) for people to clear before they could get into housing. What practitioners have come to realize is that it's very hard to stop using drugs and alcohol, for example, when you're living on the street. Similarly, it’s very hard to get and keep a job when you're living in a car or a tent. Housing First flipped the mindset: Instead of expecting people living on the streets and in shelters to solve all of their non-housing problems, this approach immediately ends the life-threatening crisis of homelessness and simultaneously works on solving their other problems that contributed to homelessness. That represents a real sea change in thinking.

The evidence for Housing First is extraordinary. It works for roughly 9 out of every 10 people, but we do appreciate that it doesn't work for everybody. That is partially because we need to scale housing and support, which is what All In aims to do. But I think we also need to have a more creative and open conversation about what else we need in the toolbox and in the continuum of housing options. Some people, for instance, do really well with recovery housing, where (unlike with Housing First) sobriety is a requirement. So we know that we need a range of other options, but Housing First has to be a big part of that range of options. It’s one of the few evidence-based practices we have.

Warren: In your presentation, you featured a slide entitled “Housing is Healthcare.” As someone who spent a large part of their career in public and affordable housing, I was surprised that I had not heard that expression before, but it immediately made visceral sense. Can you address this linkage?

Olivet: Homelessness is inherently harmful to people’s health. Not only does homelessness worsen health, but preexisting conditions increase a person’s likelihood of experiencing it. Everything from strokes and epilepsy to dementia are more common in people who have experienced homelessness.

It is extremely hard to treat chronic medical conditions, acute medical conditions, drug and alcohol recovery when you haven't addressed the basic foundational need for a safe and stable place to sleep, when you have no kitchen to cook healthy meals, and no bathtub to bathe your children. Just try to put yourself in the shoes of that experience for a minute and imagine how you'd attend to the health of your children or your own mental and physical wellbeing when you don't know where your next meal is going to come from, when you don't know necessarily where you're going to sleep tonight, or if you're going to be safe through the night. On Maslow's hierarchy of needs, shelter is part of the first, most basic level along with air, water, and food.

Warren: In your presentation, you also mentioned that some cities and states have "right to shelter" laws that require jurisdictions to provide emergency shelter for any unhoused resident that requests it. I also understand that the number of people who are homeless is significantly higher than what might otherwise be plainly visible because approximately 60% of the homeless population is estimated to be living in shelters or in other temporary housing.

Olivet: The conversation we really need to be having is how to operationalize a right to housing. Right to shelter jurisdictions have invested pretty heavily in shelter, and that's important for keeping people alive and giving them a temporary safe place to be — although shelters can be a mixed bag. Shelters, however, don't solve homelessness. What we need to do is dramatically shorten the length of stay in shelter and create better pathways to housing and service solutions. This requires scaling up the housing and the wraparound supports that are necessary to help people remain stably housed.

To this end, there are a couple of things this administration is specifically doing in terms of “unsheltered homelessness,” the portion of the population living in cars, streets, or tents. HUD is investing hundreds of millions of dollars in communities to explicitly address unsheltered homelessness, and I think that's going to be a really important tool. In addition, USICH and the White House are set to launch a new initiative to help targeted cities and states implement All In and test new models to get people off the streets and into homes.

While there’s a lot of room for innovation, we know that criminalization doesn't work. It is ineffective, expensive, and inhumane. Unfortunately, more and more cities and states are resorting to it as they face public pressure to do something about the tents that people see in their neighborhoods and on their way to work. But we cannot arrest our way out of homelessness.

Where are people supposed to go? In many communities, there is little affordable housing, and shelters are full or turn away people who are not sober, people who identify as LGBTQ+, and people with partners, pets, or teenage kids. We need to dramatically ramp up our investments in housing and expand the supply of and access to affordable housing and low-barrier shelter.

It doesn't work just to sweep an encampment and hope it doesn't pop up somewhere else. If you're not providing housing and services for people, then it's like playing whack-a-mole: the encampment will go away here, but then it pops up over there. And now all you've done is displace people, disconnect them from services and support, and anger not just one neighborhood but two because the encampment simply moved.

Warren: In many areas, the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated strategies and forced innovation was required. What did the pandemic teach us about homelessness and its solutions? Do you have confidence that we’ve integrated the learning into the work?

Olivet: In the beginning of the pandemic we were all told to stay home. But not everybody has that, right? Not everybody could. And people without a home — especially if they were living in congregate shelters and other settings with hundreds of people — were at incredibly high risk for contracting and dying from COVID-19. So there was a massive mobilization by public health people, by Health Care for the Homeless people, and by our shelter systems to keep people safe. In many places, that was just the start of what are now broad and ongoing partnerships between health and homeless systems. That's a real success story.

The pandemic also forced us to reimagine and decongregate shelters. Many communities used American Rescue Plan funding to convert vacant hotels and motels into non-congregate shelters where people without a home could socially distance. This was an extraordinarily effective approach, and some communities and states are now converting the shelters into permanent housing. That was an incredible innovation.

We also saw an easing of government regulations that was really useful. I think we need to do some real soul searching now around what bureaucratic requirements are necessary.

The pandemic also proved the power of prevention and the impact of getting money into people’s pockets. Emergency rental assistance prevented more than 1 million households from losing their homes and it prevented an overall spike in evictions. Meanwhile, the stimulus checks and expanded child tax credits significantly reduced poverty — and this all happened during a time of economic crisis, proving that we can make progress even in the most difficult times.

Our response to the pandemic prevented what could have been a tsunami of new homelessness. In reality, between 2020 and 2022, homelessness flattened out. It had been increasing since 2016, but the Biden administration halted the rapid rise and is now working to reduce it 25% by 2025. The flattening of the curve was no accident. It was the result of unprecedented federal investment.

Warren: How much of this innovation do you think is temporary, brought to bear to meet the need of the hour? Have you seen new stakeholders come in to help solve the problem and have they stayed invested?

Olivet: I think the jury is still out. I do know that we need the private sector to step up in a different way — the corporate sector and the philanthropic sector, including corporate social responsibility programs. We are seeing communities where private money invests in innovative solutions, and that needs to continue. I think many corporate leaders are seeing the impact of homelessness on the overall perception of what a healthy community is and on the overall economics of what it means to have a small business downtown or to run a corporation.

Both the availability and the cost of housing can drive your own workforce out of the area that you're based in. So I think there's some neuro-connectivity between these issues on the part of folks in the corporate sector, and I think that's wonderful. I would just issue a call for leaders in the corporate sector to step up and also to be part of the solution on homelessness.

Warren: The Social Impact Review is a social impact journal focused on ideas and solutions for advancing the thinking and problem solving by practitioners on some of the world’s thorniest, most complex problems. Do you believe we can and will solve homelessness in your lifetime? Can and will — two very different questions.

Olivet: I'm Intensely optimistic that we can solve homelessness if we choose to. And I say that very carefully. This nation has proved extraordinary at its ability to tackle really challenging problems. It's also clear that to do that, we need public and political will. And we need resources. We can't just hope the problem goes away.

The problem of homelessness has cycled through the history of the U.S. and that’s true even in the colonial era on this continent. So it's an old problem and it's deeply entrenched. In the last 50 years, as contemporary homelessness has really risen and gotten entrenched on the American landscape, that it could seem overwhelming, but it doesn't have to be this way. We know what it would take to end homelessness. We've got enough money. We've got enough creativity. We've got enough amazing people. I believe our plan lays out a lot of those ambitious approaches. I think we can absolutely end homelessness if we choose to as a nation. There's enough resilience in the lives of people who are experiencing homelessness, so much strength there, and so much ability to navigate really complex situations. We just have to put it all together and then we scale up what's working to meet the need. It all starts with preventing homelessness before it ever happens. Down to my core, I believe we can do all that.

About the Author:

Paige Warren is a 2021 Harvard ALI Senior Fellow and senior editor for the Social Impact Review. Paige had a distinguished career in financial services at the nexus of business, government, and neighborhoods. Over the course of her 17-year tenure in the commercial debt side of Prudential Financial’s investment management arm, Paige served in various senior roles including Global COO and Head of Strategy, President, and Portfolio Manager.

Much of Paige’s career was spent in affordable and public housing development and finance. Prior to joining Prudential, she served in the Federal Government to build an organization focused on restructuring the government’s affordable multifamily housing debt. She has served in various other private sector roles, including that of developer, investor, and feasibility consultant.

Paige is currently the vice chair of the board of trustees and chair of the finance subcommittee at The Washington Center, a non-profit, higher education adjacent organization whose mission is to enhance the pipeline of diverse talent and to build more equitable, inclusive workplaces and communities. She is an ESG FSA Credential-holder and holds a certification in ESG Investment from the CFA Institute.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.